Rafting on the Klamath River before the recent dam release. (Photo: Matkatamiba via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED)

The rivers of the west dominate their landscapes, from mountains to canyons. They are critical habitats for fish, amphibians, and fowl. They are also central to the histories and present cultures of the region's many Indigenous tribes. The Klamath River is among these watery landmarks. However, its powerful flow has been severely hampered by a series of dams built during the 20th century—dams which have interrupted the breeding patterns of the salmon which were once abundant. Now, thanks to advocacy by Indigenous peoples and environmentalists, the dams are being removed to restore the river's natural flow.

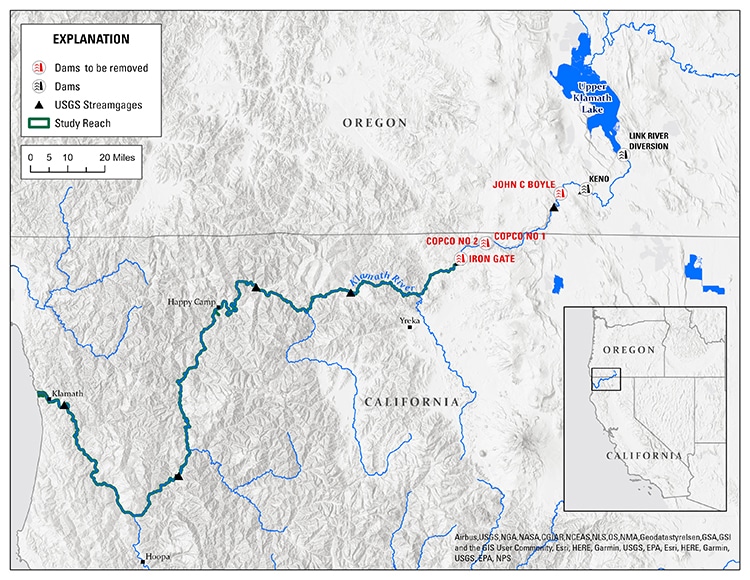

Running down from Oregon into northern California, the massive Klamath River eventually empties into the Pacific Ocean. It stretches a long 257 miles. In the past, the river was a rich breeding ground of Chinook salmon, coho salmon, and steelhead trout. These are species which swim upstream from the ocean to spawn in fresh water. They have long been critical to the survival and culture of the Yurok Tribe and other Indigenous peoples who live alongside the long flow of the river.

Between 1911 and 1962, dams were built by PacifiCorp. While holding the water back, the dams harnessed the flow for hydroelectric power. The barriers changed the natural flow of the water downstream. Without strong flow, “toxic algae and high temperatures” develop according to Save California Salmon. “They also prevent high flows needed to flush out algae that spread the fish disease—namely C. shasta, which kills the majority of juvenile salmon during low water years,” the organization highlights. These factors contributed to a massive die-off of salmon in 2002.

Indigenous activists and environmentalists have pushed for years to rectify the problem. In 2022, the concerns for the fish, as well as firefighting, bankside vegetation, and many other considerations contributed to a decision by PacifiCorp to not federally relicense their dams in the face of expensive changes needing to be made. The projects will be removed, and indeed this is ongoing. In January 2024, three dams released their pent up water, finally allowing the river to flow as it is meant to for the first time in a century. Speaking to the San Francsisco Chronicle, Frankie Myers, vice chair of the Yurok Tribe, said, “We’re now pulling the plug and throwing it away. Not to get too mushy about it but being able to look at the river flow for the first time in more than 100 years, it’s incredibly important to us. It’s what we’ve been fighting for: to see the river for itself.”

For about a century, the Klamath River's flow has been impeded by a series of dams, which have affected the ecosystem.

The Klamath River where it empties into the ocean in California. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

After much activism by Indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest, the dams are being dismantled, and the river is allowed to flow freely at last.

Map of the path of the river with the dams notated. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

h/t: [IFL Science]

Related Articles:

Fire-Scarred Redwoods Are Rebounding by Sprouting 1000-Year-Old Buds

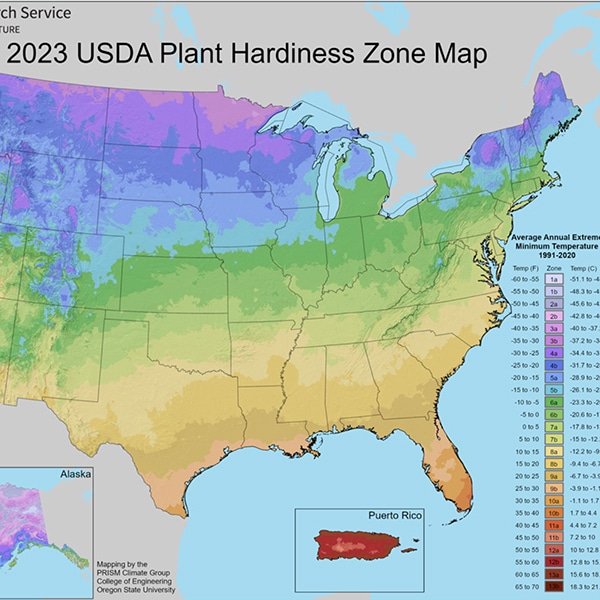

New Plant Hardiness Map Confirms Gardener Suspicions That the U.S. Has Gotten Warmer